Revisiting Communal, a zine I made during the pandemic, makes me cringe – but co-living schemes are in the news again… I had been collecting snippets of ideas that related to the idea of communal living, or informal systems of sharing and negotiation, as well as examples where this had been corrupted. Like a geodesic dome used as a climbing frame – great – but also as plastic booths on astroturf in a pub garden. Or the long tables in a restaurant that can seat twice as many covers as individual ones in the same space, but it’s sociable and French of course, not tight margins. Or the council that has wardens hide in a car park to catch and post fines to people that accept a ticket with time left on it from a kind stranger. I’ll try and share more of the examples somewhere perhaps.

There are corporate co-living buildings popping up again – and in a similar way, they’re examples of the corruption of something more idealistic. And to be clear, I’m not talking about communes, CLTs, co-ops, self-builds, multi-generational, collective or any kind of ground-up equitable development. I mean a top-down model where you can rent a studio for a year, like student halls, no pets and don’t leave personal belongings in shared areas.

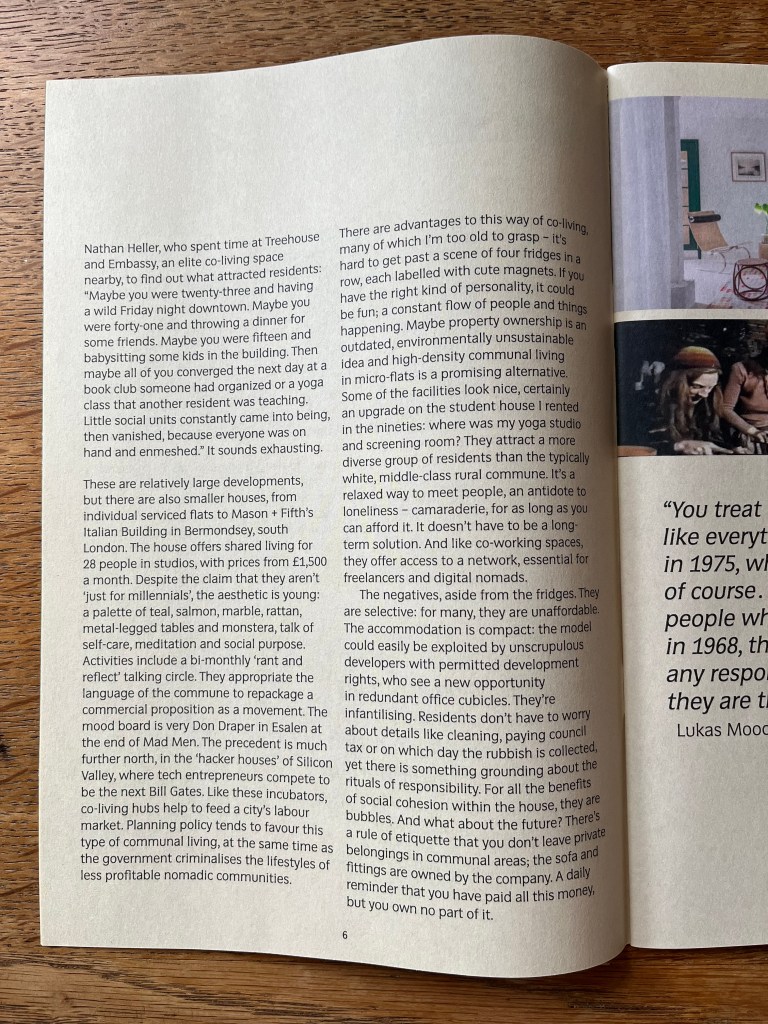

It’s not that the spaces themselves look unappealing – on the whole they don’t. They’re not to my taste, but they look fine. Some have great architects, who have done interesting things with the brief they were given. But one thing I found particularly jarring then was the appropriation of the language of the commune, and the way it was being used to sell a commercial proposition as a movement.

Not that I’m massively into the idea of living in a commune myself, but I like what collectives try to achieve and find the spaces that come from people working together inspiring. See my review of Londoners Making London. The zine included Bonnington Square’s beautiful community gardens, some allotments, an interview with one of the founders of Library of Things. I had Max Lamb in ‘designer potatoes’, posing with his vegetables on a plot Gemma, Max and Ivo cultivate with a neighbour, a piece by Rowland Byass on gay retirement living in Mexico.

The latest revival of co-living isn’t fresh political will, so much as the nature of the project pipeline; a raft of office conversions and schemes completing and their press being picked up. There’s a good piece in the Architects’ Journal about one of these new builds, but two things stuck out from the interviews as bleak. The point that for investors, “the operational income is higher than a traditional build-to-rent return.” No need for pesky impediments like space standards. One architect adds that developers see “office-to-co-living conversions as a huge emerging opportunity.” That went well in Croydon with Delta Point etc didn’t it, as Peter Apps explains. Recycling redundant offices for housing could be useful, if done well with a more generous, equitable approach to space, inside and out.

There was a really good piece by Nathan Heller in the New Yorker at the time, where he spent time in different co-living set ups and observed their social schedule. There’s something about that constant yoga-jog-ceramics-studio cycle of self-improvement that made them feel even more like a workforce factory farm. We get rightly angry about insecure employment contracts with their lack of sickness/caring benefits, but the contract for the latest co-living ‘home’ seems to be 3-12 months. You can renew of course.

Maybe in some circumstances, this kind of super sociable living, temporary contracts and an infantilising lack of responsibilities for such mundane things as utility bills might have its place. In a fair housing market, these might be one reasonable, perhaps even desirable, option among a variety of alternatives. But the point is the lack of alternatives, because I’m lucky to be old, lucky not to have to deal with renting at this point. Co-living still feels like dressing up a housing crisis as a lifestyle choice.

Here’s the original piece…