Review of The Brutalist: Building Design & Building Magazine, January 2025

[Includes plot details]

I didn’t go to see The Brutalist at the Barbican, but at the Curzon Mayfair. Its coffered ceilings and bas-relief walls aren’t Brutalist, no. But given the cinema’s battles against development, it felt right for a film based around preserving the integrity of an architectural vision against commercial forces. And it’s nice, isn’t it.

This willingness to indulge technical inaccuracies is significant because The Brutalist isn’t really about Brutalism either. Architecture is the device to explore wider themes of trauma, the Holocaust, migration, addiction, marriage, art and power.

The film tells the story of Hungarian-Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor, László Tóth, played by Adrian Brody. He sails to the USA to rebuild his life after the war. In the first part, we follow his struggles as he moves from New York to Pennsylvania, where his cousin has a furniture shop. His fortunes change when he meets wealthy industrialist, Harrison Lee Van Buren, played with unsettling mercurial menace by Guy Pearce.

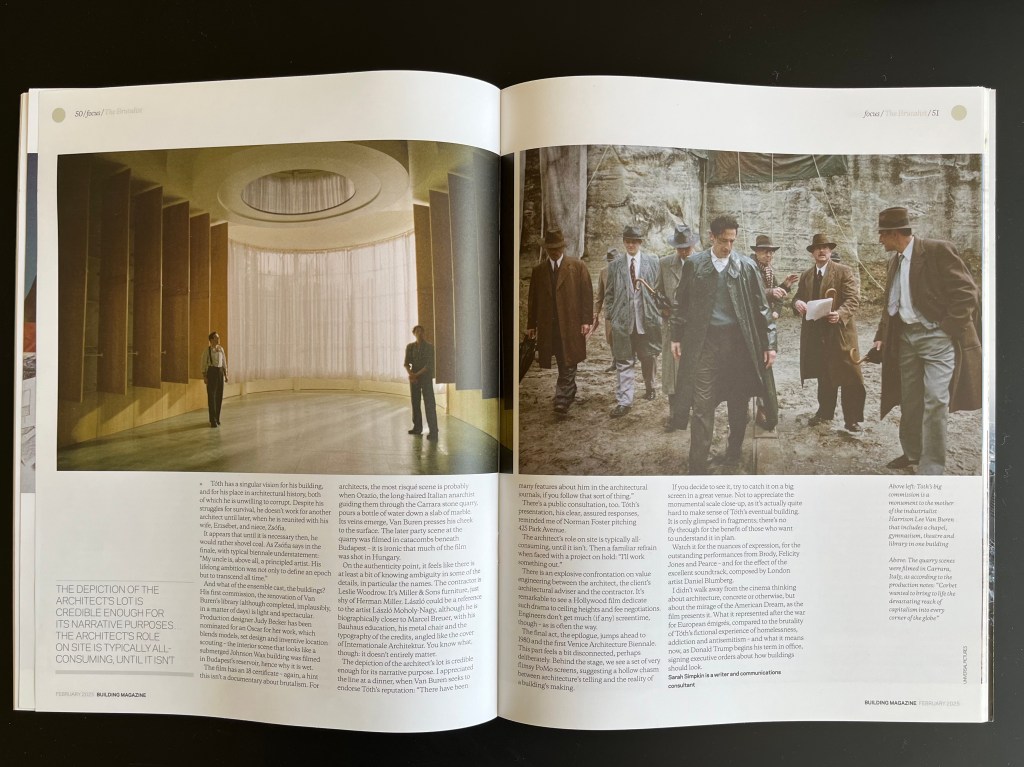

Without ruining the plot too much, Tóth gets his big commission: a monumental building on the summit of a hill, as a tribute to Van Buren’s mother. The brief is for a gymnasium, chapel, theatre and library in a single building. His design concept for this multifunctional memorial seems to rest entirely on some high concrete walls and a simple, Ando-ish crucifix of light.

The architects I’ve spoken to about the film have gone straight for its inaccuracies. I was told an Ayn Rand-style hero with a glory project misrepresents Brutalism’s social ideals. Another critiqued the water in the building – “why?” It bears saying that this is fiction, not a documentary. In the same way that the houses of Lannister and Stark aren’t an accurate retelling of the Wars of the Roses.

The film is in four sections – overture, two parts divided by an interval, then epilogue – and this first act could be seen as a straightforward story of wish fulfilment for some: your talent is discovered by a wealthy patron, who rewards your (lone, male) genius with carte blanche on a big cultural project. There are built instances of it happening, but I can see how architects trapped in today’s procurement riddle of having to prove you’ve built something before you get an opportunity to try, might bristle…

Read the full piece on Building Design or Building.